Where the Dogs are Buried

When New Japan Introduced Us to Soviet Wrestling and the World’s Greatest Freestyle System

Originally publish on FightGameMedia.com

Where the Dogs are Buried: When New Japan Introduced Us to Soviet Wrestling and the World’s Greatest Freestyle System

“That’s where the dog is buried.”

—Russian phrase used when one finally uncovers the truth about something or gets to the crux of a problem or issue.

The Soviets had long established their dominance over Olympic sports, but by the winter of 1988, the Soviet Union had found itself in deep economic trouble. The Kremlin was inevitably forced to lease out its incredibly successful sports programs to foreign nations for exhibition games to generate funds. Showcasing their superior athletes in foreign countries not only allowed the USSR to bring in revenue, but also allowed Russia to use its competitors to propagate the idea that the Soviet system created world-class athletes. The first to take the Kremlin up on their offer was Antonio Inoki and New Japan Pro Wrestling.

1988 was not a successful year for NJPW at the box office. A year after the famed Ganryujima Island fight between Inoki and Masa Saito, the company was in need of a new direction. 1989 would provide New Japan with some of Inoki’s most successful experiments, like putting junior heavyweight sensation Keichi Yamada under the manga-inspired hood of Jushin Thunder Liger, and later putting the IWGP title on American Leon White, who had by then been transformed into Big Van Vader.

As much as Inoki enjoyed the more fantastic elements of the business, his heart belonged to the craft of pro wrestling and particularly establishing realism in the ring. Even twenty years before Inokism changed the face of the company, Inoki was always in search of legitimate warriors. A deal with the Soviets would allow Inoki to showcase a different form of wrestling to his fanbase.

NJPW had a great deal of success converting Freestyle and Greco-Roman wrestlers into “Strong Style” grapplers per Inoki. Most of the New Japan roster had Freestyle and/or Judo backgrounds. Booker Riki Chosu represented South Korea in the 1972 Olympics. Inoki believed that his wrestling style was more translatable to athletes with legit combat sports backgrounds. The Soviets agreed and sent a contingent of grapplers to train in the New Japan Dojo with hopes of debuting them in 1989.

Warrior Culture in North Ossetia

“It’s a warrior culture. Combat has been part of the region for centuries, but now we don’t fight wars with our hands. That hasn’t changed people in the region. It’s just been transferred into combat sports. It’s how honor and manliness are determined. It’s just a different culture with a different set of values.”

Bryan Medlin is the head coach of the University of Illinois Regional Training Center. For the past five years, he has taken a contingent of athletes to live and train in the North Ossetian city of Vladikavkaz in the Caucasus Mountains. Medlin is a student of how the Russian training system shaped this World Class amateur wrestling program.

“You show up to practice in this gym in Vladikavkaz, and there’s four mats set up. There’s kids 8–10 years old training alongside World and Olympic champions. That’s how it is here. You find your club and your coach, and you train with them for your career. These kids come to practice every day, and all they want is to be a World Champion, and from day one, they’re taught, you’re gonna be a world champion. They don’t care about state titles or silly tournaments. They have that one goal because if they win a World or Olympic title, the state is going to take care of them for the rest of their lives. This is their way out of poverty.”

This was the same environment that reared a young Victor Zangiev. Though Zangiev grew up in the USSR instead of the modern Russian Federation, much of life in North Ossetia was the same. Zangiev dedicated himself to Freestyle wrestling at a young age, becoming a standout performer in the region. Boarded by Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia on the south, Ossetia has been a hub of combat sports, particularly Freestyle wrestling. The beautiful yet rugged countryside has been home to countless World Champions. The Christian state often competes with the Islamic Dagestan region to claim which state develops the best wrestlers. Considering the USSR/Russian Federation has produced more than 60 Gold Medalists since 1952 (that’s just Olympics—not World Champions), it is impossible to argue with their results.

Like all of the boys training in Vladikavkaz, Zangiev eyed World and Olympic success and began his International career winning a FILA (the international governing body now known as UWW) Junior World Championship in 1981. At twenty, Zangiev was on the older side of the age group but followed up his World Championship with a Junior European title in 1982. However, even as a Junior World Champion, Zangiev faced a stiff road toward making a Senior-level World/Olympic team.

The USSR was significantly larger than the current Russian Federation. Independent nations Azerbaijan, Georgia, Latvia, Ukraine, Lithuania, Armenia, Estonia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan were all part of the old Soviet Union. All competed to make one Soviet team. The USSR Championship tournament was frequently more difficult than the World Championships or even the Olympic Games, depending on the year or weight-class. Today, each of those nations has its own highly successful Freestyle and Greco programs, especially Azerbaijan. It also isn’t uncommon to see Russian athletes defect to one of these former Soviet block countries for the opportunity to compete in the Worlds.

In the 1980s, this was not an option for Victor Zangiev. Politics also played a role in determining World team membership. Though the USSR Championships and Olympic teams trials were supposed to set the contingents, the country made sure its “best” wrestler had the position. The idea was to place the best possible team on the mat. The American system is different. If a wrestler wins at the Olympic trials, the spot is theirs.

It’s a remarkable turn for an athlete who, a year prior, had never seen a professional wrestling match.

The situation for Zangiev was challenging. At 100 kg (220 lbs.), he saw Ilya Mate, a Ukrainian who won World titles in 1979 and 1982. Mate also won Gold at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, missing a potential match with American Russ Hellickson. But in 1983, the USSR sent Aslan Khadartsev, another Ossetian, who won the World Title at the weight and would repeat in 1986. At 22, with an aging Mate and a reigning World Champion in Khadarstev, Zangiev’s best chance to make the team would have been 1984 at the Los Angeles Games. However, the USSR decided to boycott those Games, and the US team went on to dominate the field.

In 1985, Zangiev took silver in the World Cup event in Toledo, Ohio, but failed to make the USSR World Team. 21-year-old Georgian Leri Khabelov won the spot and earned his first of six World Championships and 2 Olympic medals (Silver in 88 and Gold in 92). As a former Junior World Champion, Zangiev had no clear path toward his Olympic goals. In today’s world, Mate (Ukraine) and Khabelov (Georgia) would have represented different countries. Though getting through Khadartsev, who traded World team positions and Gold medals with Khabelov, would have been difficult. Zangiev would also have the option today of defecting, though as Ossetian, that might have been unlikely.

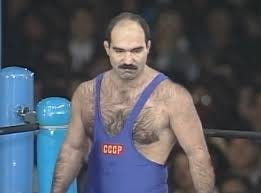

Zangiev was a World-class athlete who didn’t have a position or opportunity to showcase his talents. Until Antonio Inoki came into play. Zangiev, along with Salman Hashimikov (a Chechen who won four Senior-level World Champions), Vladimir Berkovich, and Habieli Victachev signed deals to work with Inoki and New Japan on December 20th, 1988. They were joined by 1972 Olympic Gold Medalist judoka Shota Chochishvili.

Russian Strong Style

After only two months of training, members of the Russian contingent debuted for New Japan on February 22 at Sumo Hall in Ryogoku. Zangiev wrestled Hashimikov, a long-time friend, to a time limit draw. The two would form a popular tag team later in the year. Later in the card, Zangiev defeated young lion Osamu Matsuda who would achieve fame under the name El Samurai.

In April of 1989, Zangeiv would participate in the Tokyo Dome IWGP Championship title tournament, defeating American Buzz Sawyer in the first round before losing to Shinya Hashimoto in the second round. Sawyer, a veteran of the US territory system who won an American folkstyle wrestling state title in Florida, had a unique opportunity with Zangiev. The Japanese crowd marveled as the American and Russian bowed up to each other early in the match. The crowd felt the cold war intensity. Sawyer and Zangiev begin a simple pummel drill, in which both men try to dig under hooks on each other. Amateur Wrestling 101. The Japanese fans, who had been educated by Inoki to respect different wrestling styles competing against each other, were in awe watching a Freestyle wrestler doing Freestyle wrestling in the ring.

What Zangiev and Hashimikov did for New Japan was technically closer to Hackenschmidt and Gotch than anything going on in the US at the time.

Sawyer took Zangiev down with an arm drag (the amateur wrestling version of the move, not the pro wrestling version popularized by Ricky Steamboat). Zangiev escaped and hit an arm spin throw on Sawyer as the crowd cheered. At one point, Zangiev secured a trap-arm body lock and hits what pro wrestling fans would call a “belly-to-belly suplex,” or “front suplex” in Japanese puroresu parlance. But Zangiev displayed the cleaner, amateur wrestling variation where the hips move inside the opponent’s base as the thrower back arches, taking his opponent over the top with ease and no loss of control. In pro wrestling, the thrower often releases the hold, sending the victim flying through the air. The amateur wrestling version is different: The thrower maintains control for the duration of the move, landing the throwee more safely onto the mat. Sawyer played up the theatrics and acted like Zangiev hit him with a truck. Zangiev eventually landed a bridging German suplex, called a “back sup” (pronounced just like “soup”) in amateur circles, and pinned Sawyer.

Zangiev’s match with Shinya Hashimoto allowed for the Ossetian to showcase even more of his Freestyle skills. First, he took Hashimoto down with a sweep single leg takedown. This basic yet remarkably effective amateur wrestling move again wows the crowd. Zangiev secures his opponent’s bicep with one hand and wrist with the other. It’s a position called a “2-on-1” or “The Russian Arm Tie.” Zangiev then slides into a Russian variation of the fireman carry. Though Zangiev front suplexed Hashimoto, the Japanese legend won the match in the end, allowing him to advance in the tournament. The crowd had taken to Zangiev, though. This was clear. It’s a remarkable turn for an athlete who, a year prior, had never seen a professional wrestling match.

The New Japan Dojo intelligently trained the Russians for pro wrestling by adapting their already-honed amateur skills, then teaching them how to “work” with their opponents. Rather than Kurt Angle learning in the American pro wrestling style, the Russians were allowed to do what they do best and represent themselves as Freestyle wrestlers. Their matches are all relatively short and could be categorized as “worked shoots,” but the lack of striking takes away any MMA aspect. What Zangiev and Hashimikov did for New Japan was technically closer to Hackenschmidt and Gotch than anything going on in the US at the time. They exhibit traditional wrestling moves in a worked environment, showing something different than what New Japan fans had seen up to that point. And so, Russian Strong Style was born.

The idea of throwing a legitimate match is antithetical to the Ossetian belief structure. Even still, Zangiev quickly understood the showmanship aspect to professional wrestling. Though Zangiev wasn’t outwardly emotional in the ring, he had a unique charisma that charms fans. The Japanese crowd was open and intrigued; they really tried to understand the Russians’ character, their stoicism in-ring, and how it connected to the Russians’ ultra-focused intensity. Had Zangiev been born in a different country or a different era, he would have been a natural in pro wrestling and could have had a storied career, easily. As a proud Ossetian performing wrestling instead of competing was why Zangiev never truly integrated himself into the professional wrestling mix, though he seemed to be having a great time. Zangiev was so popular with and memorable to Japanese fans that he would later become the inspiration for character called “Zangief” of CAPCOM’s Street Fighter video game series.

Zangiev spent most of his New Japan career in matches with American Brad Rheingans. Rheingans, himself an Olympic Silver Medalist in Greco-Roman, had a firm grasp on Zangiev’s fundamentals. The two had fantastic chemistry. Their matches played more like Freestyle vs. Greco-Roman exhibitions than traditional pro wrestling and were well received. The Cold War implications were an added bonus that gave the rivalry an extra boost.

Meanwhile, Zangiev’s friend Hashimikov was pushed to the top of the company, defeating Inoki’s greatest creation, Big Van Vader, for the IWGP Championship. Hashimikov became the first natural-born Russian to hold a professional wrestling World Championship since George Hackenschmidt. Hashimikov was also the first person to hold World Championships in Freestyle and Pro Wrestling. Kurt Angle would achieve the same feat in 2001. Though Hashimikov wasn’t quite as good as Zangiev in the ring, his background as a four-time world champion and his stocky build were a better fit for Inoki’s company at the time. Hashimikov would lose the IWGP championship to Riki Choshu just 48 days later.

Life after NJPW: UWFi, Street Fighter II

Inoki’s grand experiment with the Russian competitors culminated when New Japan, in alliance with the Soviet Union, hosting a special New Year’s Eve event at Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow. It was the first pro wrestling event in the country’s history and took place about a year after Inoki inked the initial deal with the Kremlin. In the main event, Inoki teamed with Shota Chochishvili, the 1972 Olympic Gold Medalist in Judo, to take on Rheingans and long-time Inoki rival, Masa Saito. Inoki did the bulk of the work here, but Chochishvili, wearing a full gi, came in to hit the heels with his famed koshi-guruma throw. To American eyes, it may have looked like a simple headlock takeover, but this Russian crowd understood it as a legitimate match finisher, or Ippon in judo. Inoki and Chochishvili celebrated the historic victory afterwards. As for Zangiev, he lost on the undercard to IWGP Heavyweight Champion at the time, Riki Choshu.

Zangiev and Hashimikov would team together in 1990, representing the USSR in the Pat O’Connor Memorial Tournament at WCW Starrcade 1990. The St. Louis crowd didn’t understand the broader implications of having legitimate Soviet champions competing in WCW, which is a shame. The Russian team won in the first round before falling to Saito and the Great Muta in the semi-finals. Zangiev, in particular, looked very good in these matches.

The Russian wrestlers left New Japan shortly after this, which happens to coincide with the fall of the Soviet Union. Zangiev would return to Japan and work matches for the UWFi shortly after the NJPW run, which was a good stylistic fit as he fit well into the company’s particular “worked shoot” style of wrestling. He would come up short of his challenge to Nobuhiko Takada for the UWFi Championship, and by 1994, Victor Zangiev quietly retired from professional wrestling.

Over the ensuing decades, pro wrestling has seen a rise in the popularity of traditional amateur wrestling throws. From All Japan’s Kento Miyahara and his highly-protected Shutdown German suplex, to Tay Conti reintroducing the AEW audience to judo’s Drop Seoi Nage arm throw, it’s interesting to think about the influence someone like Victor Zangiev has had on the current product. Fortunately, his legend and visage live on in Street Fighter lore, and to a greater extent, he and the Russian wrestling contingent were where these proverbial dogs of war were “buried” in the end. It was the earliest remnant of Inokism, but not the last. In 2021, though, fans now live with over three decades worth of “fight literacy,” established in the late ’90s and early ’00s during the MMA boom with the rise of UFC and PRIDE. With 2021 eyes, we can see just how ahead of their time Zangiev and the Russians were, and how wrestling might finally be able to return to a more realistic and pure style, using real athletes and proven grappling technique in order to tell more intense, more dramatic stories. The dogs are buried, sure, but they aren’t dead; they never were.